My husband gasped when he came into my apartment for the first time. The room was filled with stinkbugs. I had the window open, and the screen was broken. Supposedly, I told him that “they’re like friends” as a sort of defense. The bugs didn’t bother me at all.

Even now, if I’m inside and all the windows are closed, I feel claustrophobic, as if I’m being cut off from the outside world. When I lived in Ohio, the snowy winters—with their 20-degree nights—proved problematic because I couldn’t bear to be in a room without cracking a window, even if just a sliver. To feel real air.

My need for the natural world is largely due to growing up in a moldy house in the redwoods of Northern California, in a family with little discernment over things being dirty or clean. Multiple times a day, my father, a gardener who worked outside in our yard most days, would trudge all over the house with his shoes caked in mud whenever he came in to go to the bathroom or make a sandwich. My mother, who doesn’t like to clean in the first place, quite logically gave up on trying to keep the outdoors out.

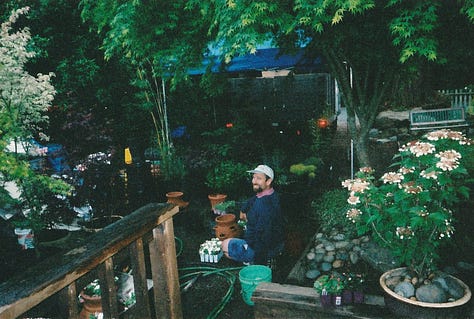

Our quarter-acre yard was filled with thousands of plants growing in black plastic pots: Japanese Maples, Black Bamboo, a large quantity of California natives. My sister and I were taught how to replant everything as soon as we could walk, and how to grow things from cuttings, how to make a mound when planting a Japanese Maple so that it would drain properly. Since the age of seven, I would go to flea markets with my dad to sell all of the plants growing in our backyard.

My sister and I were quizzed on both scientific and common names, which were verified by a worn, water-logged copy of Sunset Western Garden, a book that my father carried around like the Bible. He was self-taught and never had any formal education, but he knew the names of everything.

“Name that!” he’d call out as he pointed to a plant. My sister and I would try to think of the tree, flower, or shrub he was pointing to, competing for a hard-won dollar. Though we hardly ever won. He mostly asked us the names of new plants we’d never heard of before. He was a man of wonder; he could never learn enough.

Achillea millefolium. Yarrow. Epilobium canum. California fuchsia. Sequoia sempervirens. Coastal redwoods.

Now when I go for walks in the evenings, I grasp for the names of flowers. I forget to take my shoes off when I come inside, my shoes muddy from watering the lawn.

All of my roommates, including my husband, berate me for leaving doors and windows open in malevolent weather. Or for bringing dirt and sand into the house or car. I could see how it could be shocking to find clumps of dirt on a clean floor, though I hardly ever notice. My sister and I struggle over normal procedures of personal hygiene; each of our first partners taught us to wash ourselves properly, to brush our teeth for the correct amount of time. We were, my husband suggested, somewhat feral. The description suited us and we’ve never minded it.

When either my sister or I feels stressed, we throw ourselves into gardening. We relandscape our yards even though we’re renting. Dig our nails into the soil, spend the day weeding until our bodies ache all over. I trim trees in the yard with pruners and my husband’s reciprocating saw. Forgive me, I ask the tree, the weeds. I feel a shock as I prune some vines; their flesh feels so alive. Forgive me. Forgive me.

Afterwards, every muscle in my body is exhausted, every ounce of potential energy used. I fall into a chair the way our father used to, barely able to move. When I dream, I dream of vines.

There is a scientific theory called panpsychism, which considers consciousness a fundamental aspect of reality. This is what I am certain of, as I garden: that everything is conscious, the whole living world. That everything is alive.

Of all the places I’ve been, this theory—that everything is conscious—feels most true in Hawaii. There, everything hums with being; each palm leaf seems to flutter in the sky with great intention, as if in rhythm with the roll of waves, the call of birds.

My father gardened in Hawaii in his twenties, where he began to learn the names of plants and how to grow them. The first time I went to Hawaii was a year after he died of cancer, and since then I’ve been able to visit every year for the last five years. Every year, I wonder if I will be able to go back, and every year, an affordable means always comes through; an invitation to house-sit, or visit friends. Each time, I seem to have just enough travel points to cover my ticket and to stay on one of the islands for free.

I make grand plans as to all the writing I will accomplish whenever I go. But when I get there, my body wants only to sit outside and stare at the trees, to listen to the birds. To float in the ocean like an animal, one with the earth.

I do write, of course, but out of a place of rest. Time becomes spacious, unlimited, and I write slowly, as if inhaling deeply from my diaphragm. The leaves appear to be breathing as the wind sways everything around me. It rains for one hour and is sunny the next. Almost every moment, I am filled with gratitude and awe.

When I come home, as I came home a week ago, I feel certain that my real self is still on the island, searching unhurriedly for words. Already, when I sit down to work again, time begins to shrink instead of expand, and I worry over the progress I am making on my novel. How it is not nearly enough, how it feels as if I will never finish.

I go back outside into the garden and begin trimming the plants. Thank you, I tell them. Thank you. I feel gratitude and wonder in every muscle of my body, down to my bones. I water, tug, and trim until I am exhausted again. When I come back into the house hours later, I drink a large glass of water and call my sister to ask about her lemon tree. Citrus limon. I fall asleep next to my husband in bed, like a warm animal. This is real life, I remember, clasping his body in my hands like soil. Like dirt. Dust to dust.